Mayor-elect Eric Adams has vowed to make New York City “the center of the cryptocurrency industry” as part of a broader effort to appeal to businesses.

Cryptocurrencies and their fundamental technology, blockchain, have fueled a boom in investing over the past decade, culminating in the gold rush this year over non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, digital image tokens that use blockchain technology.

Adams has been scarce with details over how he wants to position the city, already a global financial center, as a hub for cryptocurrencies.

His interest in the digital coins has already come under scrutiny. Last month, he was found to have flown to a political conference in Puerto Rico on the jet of Brock Pierce, a major cryptocurrency evangelist who controversially had planned to make the territory into a cryptocurrency hub, after first claiming that he paid his own way. A spokesperson for Adams said that the mayor-elect paid for the flight, but Adams has not produced a receipt for it.

Here are some answers on what Adams’ cryptocurrency plans could mean for New York City.

New York City Mayor-elect Eric Adams smiles at supporters, late Tuesday, Nov. 2, 2021, in New York, after the mayoral election was called in his favor. (AP Photo/Frank Franklin II)

Please remind me — okay, fine, tell me — what cryptocurrency is.

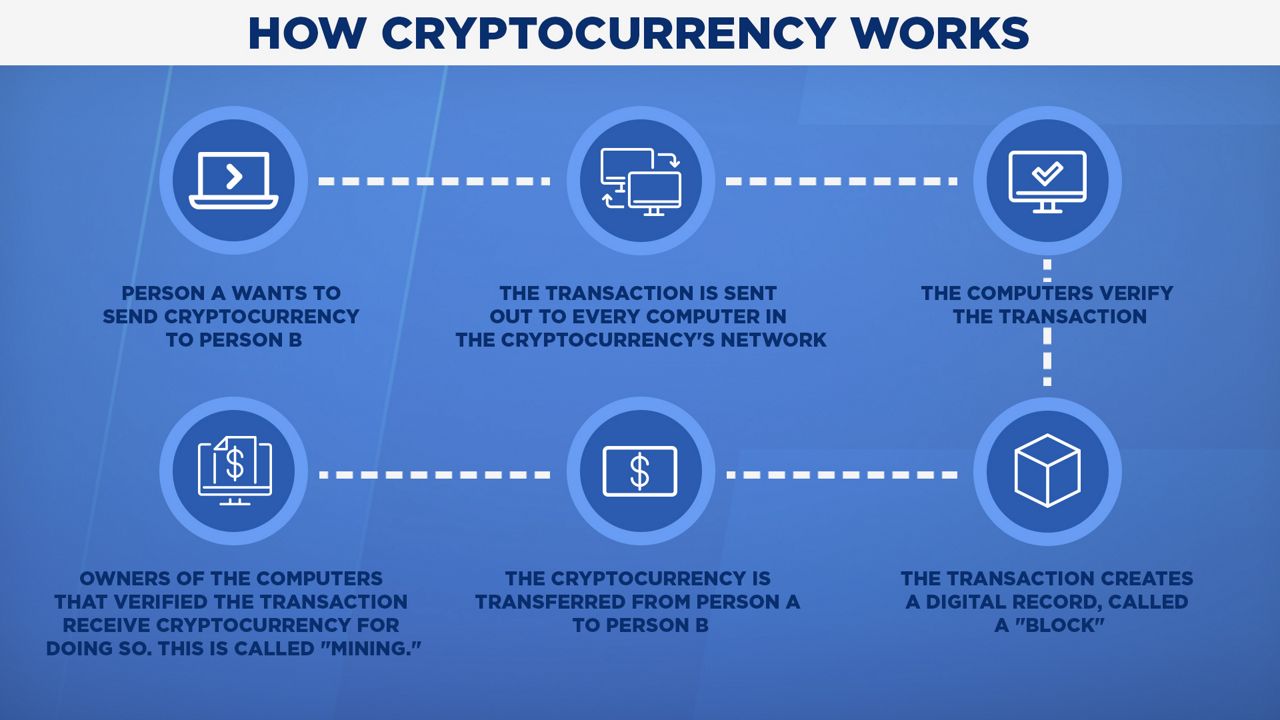

In brief: cryptocurrencies are forms of digital money. The best known is bitcoin, currently worth about $60,000 per coin, but others, like Cardano and Dogecoin, have become widely popular in the cryptocurrency investment world. They function on a technology called blockchain, in which a network of computers confirm and maintain the complete list of financial transactions made with whatever cryptocurrency you’re using.

The reason this technology is newly popular is because it offers an alternative to centralized banking, in which massive financial institutions use private technology to track payments. Cryptocurrencies use a decentralized network of privately owned computers — often grouped together in massive, energy-sucking server farms — to solve complex computer problems in order to confirm transactions. Each computer helps maintain the record of all the transactions, which is publicly available.

In exchange for doing this —running computers endlessly to maintain the cryptocurrency’s ledger — the people operating the computers get some of the cryptocurrency. This is called mining, and, when done using a cheap energy supply, it can be quite profitable.

Although the coins aren’t backed by anything — such as a government, in the case of money, or a public company’s stocks — their value is driven by buyers’ faith in the technology as a safe place to invest their money, the currencies’ relative freedom from political forces and, typically, by a constrained supply of the digital coins.

The novelty of blockchain, a technology unveiled in 2008, is that the ledger is virtually impossible to manipulate, making it immune to fraud and identity theft. In Estonia, an early adopter of blockchain, the technology allows citizens to hold all of their medical records in their digital wallet, as well as file taxes almost instantaneously. (The only public services they can’t access digital-only are getting married, getting divorced or conducting real estate transactions, according to a 2019 report.)

What has Adams said he wants to do?

Adams has been a little vague.

In a tweet last month, for instance, he said he plans to take his first three paychecks in bitcoin, even though the city does not cut paychecks in anything but U.S dollars. (He later said he will be converting his paycheck to bitcoin.)

He has also suggested bolstering financial literacy education in city public schools around cryptocurrency — something some teachers have already started on their own — and in general making the city a destination for cryptocurrency innovation.

“We’re going to turn New York City into a laboratory,” he said at a business conference last month.

How has his enthusiasm been received?

Adams’ hype has excited crypto die-hards, who have come to rely on viral interest in cryptocurrencies to drive value in the various coins.

But he is still regarded as a newcomer. Cleve Mesidor, a public policy advisor for Blockchain Association, a lobbying group, said she realized Adams was new to cryptocurrency in the spring, when he referred to “bitcoins” in plural — an ungrammatical faux pas in the crypto world.

“It was not surprising that once he was elected, he went deeper,” she said. Still, she said, “None of his ideas are new, none of them are necessarily controversial.”

Some experts see little substance in his pronouncements so far, and little evidence that he has a technical understanding of the technology. In a recent interview on CNN, he sidestepped a question about how bitcoin works to say broadly that it is a “new way of paying for goods and services throughout the entire globe.”

“I suspect he’s probably not as conversant with the details of bitcoin in particular and how it works as he is with just the fact that it has a sort of hipness and a cache to it,” said Robert Hockett, a professor of financial regulation at Cornell Law School.

A representative for Adams did not respond to an emailed list of questions.

Isn’t cryptocurrency an extremely volatile investment?

In general, yes: This year alone, bitcoin doubled from about $30,000 per coin on January 1, to $60,000 in April, then dropped back to $30,000 in July before climbing to $70,000 last month. Some cryptocurrencies, however, known as “stablecoins,” are tied to the value of the dollar to avoid massive swings in value.

For Adams, however, the volatility is par for the course.

“I’ve lost thousands of dollars in the stock market during the stock market crash in my retirement fund,” Adams recently told CNN. “Volatility is part of some of the investments that we make.”

What about the environmental cost of cryptocurrencies?

Critics of the technology say that the costs are steep. Researchers at Cambridge University have estimated that cryptocurrencies together use more energy in a year than the country of Argentina, mostly to run the computers that maintain the blockchain ledgers.

Some cryptocurrency mining companies have come under intense scrutiny for how they get the energy to run their server farms. One firm converted a retired coal plant in Dresden, N.Y., to gas power in order to generate its own electricity — enough to power 35,000 homes — to run its 15,000 mining servers. Some environmental groups have accused the firm of disrupting the local environment through discharging superheated water used to cool the servers directly into a tributary that feeds nearby Seneca Lake.

Adams has not said anything about cryptocurrency’s environmental cost. But experts say it is unlikely that firms would attempt major mining operations in the city, given the relatively high electricity costs — even though the prospect is still worrying.

“There would be a serious environmental problem too if New York became the capital of bitcoin mining,” Hockett said.

The Greenidge Generation bitcoin mining facility is in a former coal plant by Seneca Lake in Dresden, New York, on Monday, November 29, 2021. (AP Photo/Ted Shaffrey)

I assume cryptocurrencies are regulated, so how much can Adams do?

They are — in fact, New York state is one of the hardest places in the country to get a business license to buy and trade cryptocurrencies, experts say. Mesidor referred to the state’s regulations as “hostile” to cryptocurrency trading. New York’s license is called a BitLicense, and currently only 29 companies have approval through the state to trade cryptocurrencies. This year, the state’s Department of Financial Services granted only three such approvals, according to its website.

In June 2020, the DFS announced a partnership with the State University of New York to create a start-up incubator for cryptocurrency businesses called SUNY Block, which would help fast-track the start-ups’ applications for BitLicences. More than a year later, the DFS is still “in discussions” with SUNY on starting the program, according to Sophia Kim, a DFS spokesperson, and no licenses have been granted through it.

Adams would have relatively little power to change the state’s cryptocurrency trading laws and regulations — let alone the federal government’s regulations, according to David Yermack, the chair of the finance department at New York University’s Stern School of Business. Already, the head of the Securities and Exchange Commission has signaled his intent to heavily regulate cryptocurrency trading.

“The finance industry is really regulated out of Washington, not out of Gracie Mansion,” Yermack said.

One thing Adams could do, however, is create a municipal version of the technology that cryptocurrency relies on: the digital wallet.

The idea, shorthanded as a “public Venmo,” in reference to the popular payment app, would provide every citizen who wanted one with the equivalent of a bank account and a means for making instantaneous, cost-free digital payments, according to Hockett. In 2019, he drafted legislation at the state level to create such digital wallets alongside state Assemblyperson Ron Kim and state Senator Julia Salazar. The bill is currently being evaluated by the Assembly’s Banks committee.

The wallets could be used by residents wanting to pay rent, parking and other costs — as well as by vendors like bodega owners who want to accept payments — without having to also shell out the common processing fees required for credit cards. It would also reduce reliance on so-called payday lenders among working class residents, Hockett said, who typically charge large interest rates for short-term loans.

“This would be very very helpful to those who Adams claims to be his primary constituents,” Hockett said.

Would New York be the first city to get into cryptocurrency?

Hardly. Miami has already released a municipal cryptocurrency, called MiamiCoin, that already has raised millions of dollars since August for the city from people buying into the digital currency. Miami Mayor Francis Suarez expects $60 million in revenue from the coin over the next year, and has hopes that the coins’ revenue could replace municipal taxes in funding city services.

Other cities and states have lowered barriers to allowing cryptocurrency companies to incorporate there, or, in the case of Cool Valley, Mo., population 1,200, have plans to give every resident $1,000 worth of bitcoin. Earlier this year, Georgia’s state legislature passed a law that included a requirement that cryptocurrencies be taught in public high schools.

The best use for cryptocurrency in New York City, according to Mesidor, would not be through such bold moves, but rather by using blockchain technology to make city government more efficient. A public housing agency run on blockchain, for example, could include a ledger of lead paint inspections that can be viewed by the public and which can’t be manipulated.

At the same time, Mesidor said, Adams has to be careful to foster crypto innovation that includes marginalized New Yorkers, especially the Black and Latino communities who came out in force for him in the mayoral election. Those communities, she said, will want to see new jobs come out of an expanded cryptocurrency industry in the city, and not just a gold rush for wealthy, white-collar workers.

“If he starts talking about cryptocurrency in terms of skills training, in terms of focusing on small business centers and financial literacy, preparing people for jobs of the future, that’s more pragmatic,” she said.

Mesidor said she was concerned by Adams’ association with Pierce, a supposed cryptocurrency billionaire, who hatched a plan to make Puerto Rico a tax haven for owners of digital coins and who was met with strong pushback from island natives.

“Even if we focus on things that benefit constituents or give value to New Yorkers, which New Yorkers are you talking about?” she said.